When a movie adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches was released in October 2020, viewers weren’t just upset by a change to the story; they were offended.

In the film, the Grand High Witch, whose fingernails resembled cat claws in the book, had hands with only two fingers and a thumb, or split hands, a condition called ectrodactyly. To people with disabilities, the change inadvertently reinforced an all-too-common stereotype—“disability and disfigurement as visual shorthand for evildoing,” writes New York Times reporter Cara Buckley.

But disability representation issues exist in books too. And when disability is incorporated in fiction, it often falls into the same harmful stereotypes depicted in The Witches film.

So how can authors make sure their stories are truly inclusive of the disability community?

Write characters, not caricatures

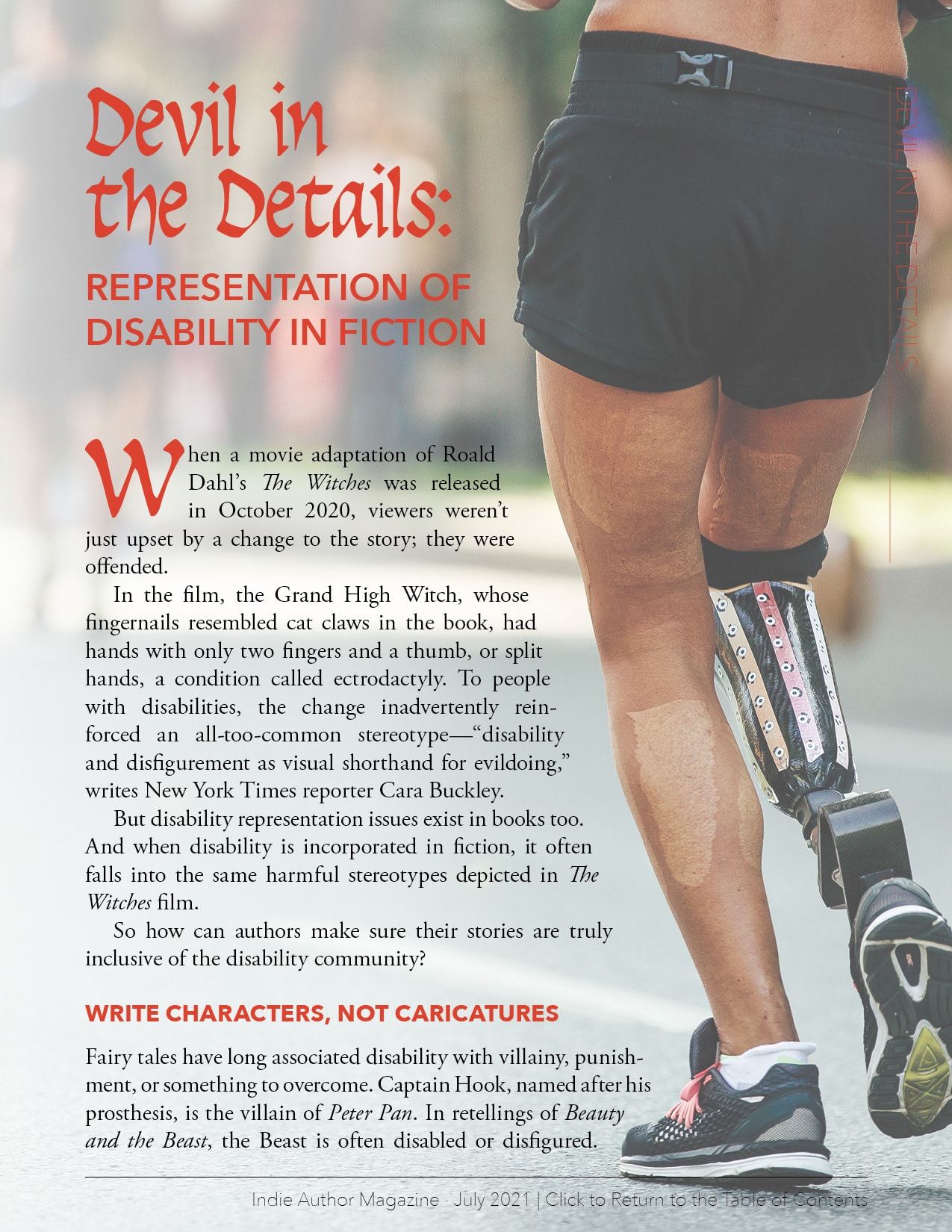

Fairy tales have long associated disability with villainy, punishment, or something to overcome. Captain Hook, named after his prosthesis, is the villain of Peter Pan. In retellings of Beauty and the Beast, the Beast is often disabled or disfigured. Stories that paint people with disabilities as inspirational simply for living are also problematic, says Madison Parrotta, senior editor at INCLUDAS Publishing. INCLUDAS, founded in 2015, publishes multiple genres, but all its books feature a main character or author with a disability.

These “inspiration” stories often remove any uniqueness or personality from the character outside of their disability, Parrotta, who is disabled, says. Without multidimensional representation for people with disabilities in media, stereotypes create real-world barriers. “That’s harmful for them because when they need help with whatever their disability entails, they might not be able to get it because people view them negatively because of the stereotypes they’ve seen.”

Watch your words

Making sure characters are fully developed—and not infantilized or pitied—is crucial to writing disability narratives well. Sometimes, Parrotta says, word choice can make a big difference. Many people who have disabilities dislike terms like “differently abled” or “wheelchair-bound” for their negative connotations.

Parrotta acknowledges it can be hard to know which terms to avoid if you’re not part of the community you’re writing about. “We’re not perfect,” she says. “I’m sure I’ve written things that are ableist.” But being conscientious of your word choice is an important first step.

Hit the books

When incorporating disability narratives in your work, do your research. Think about your character’s experiences—navigating uneven terrain with a mobility issue—or details to keep in mind, such as avoiding visual descriptions from a character who is blind. Writing realistic fiction? Learn about the legal and societal barriers people with disabilities face. World-building for your fantasy novel? People with disabilities exist there; how does their community accommodate them?

Learn from people with disabilities, and consider hiring a sensitivity reader, Parrotta says. Most importantly, ask yourself whether the story you’re writing is one you can authentically tell.

“The research is so important, but I also think taking a step back is important too,” she says. “If you want to tell a story about a main character who has a disability, and you don’t have that experience, should you really be telling that story? Ask yourself, ‘Why is it so important that you use a disabled character?’”

Writing disabled characters accurately and with nuance takes work and dedication, but it’s critical, Parrotta says. “I feel like if I’d seen more people with disabilities in the books I was reading (as a kid), I would have been a) more apt to find that community and b) accept myself for who I am as a disabled person.”

Research toolbox:

Want to learn more about writing disability inclusively? Check out these resources.

- We Need Diverse Books: The nonprofit organization compiles resources for writers and publishers that promote diversity and inclusion in literature.

- Vanessa Marie: A self-proclaimed “Booktuber,” her YouTube channel includes multiple videos dedicated to writing diverse characters, including characters with disabilities.

- Salt & Sage: Sensitivity expert consultants and readers for hire.